Love, Eventually: What Taylor Swift’s messy new album offers the heartbroken

Love, Eventually: What Taylor Swift’s messy new album offers the heartbroken

22/10/25

By Bel Kelly

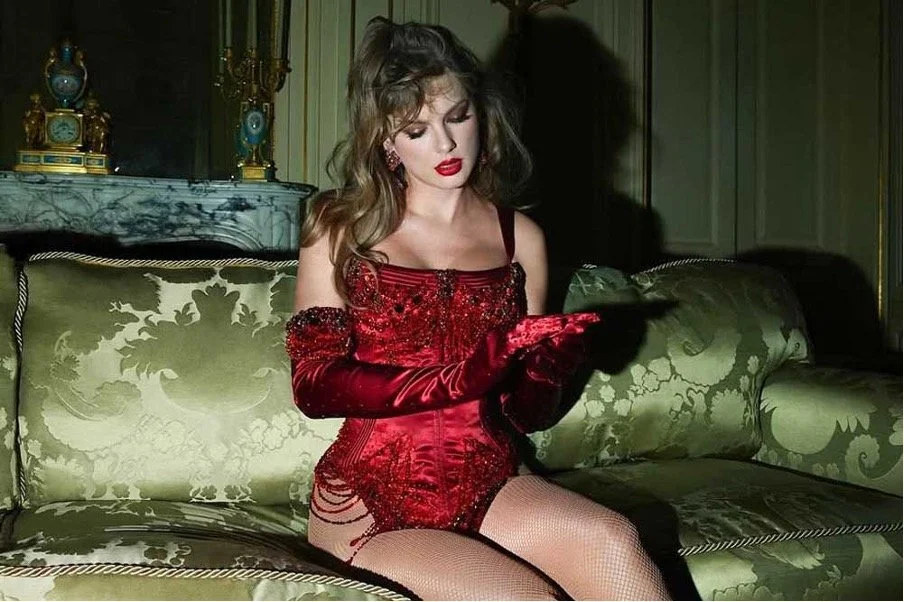

Taylor Swift’s contribution to culture: it is a topic so oversaturated, as inescapable in St Andrews magazines as it is on Twitter. Her new album, The Life of a Showgirl, has, in classic Swift fashion, inexorably dominated discourse since its release. Some claim the album marks a drastic drop in lyrical quality – so much so that some are (misogynistically) questioning whether her previous work was ghostwritten by ex-boyfriends. Others have claimed that her billionaire status has rendered her unrelatable and, therefore, arrogant. Some have gone so far as to use her new merchandise as evidence of Nazi sympathies. The album’s musical merit, lyrical value, cultural sensitivity, originality, and feminist implications, as well as Swift’s personal morality, have all been under intense, maybe even absurd, scrutiny.

It is my opinion that, much like Midnights (2022) and The Tortured Poets Department (2024), The Life of a Showgirl feels unedited and derivative. She covers the same well-worn Swiftian themes: her cancellation, feuds with female friends, desire for matrimony, and struggles with fame. The lyrics lack coherence and originality; the hooks aren’t catchy; the production sounds recycled. The only thing I was happy to remark upon after my first listen was the album’s length. At least there weren’t thirty songs this time!

Is The Life of a Showgirl a good album? No. Is it good relative to Swift’s other work? No, it doesn’t hold a candle to either the playful pop of 1989 (2014) or the sincere songwriting of evermore (2020). As put by Alex Petridis of The Guardian, “It’s just nowhere near as good as it should be given Swift’s talents, and it leaves you wondering why.”

Yet, one criticism that seems unfair to me is that this album expresses “a certain impulse toward conservatism, as the singer embraces suburban dreams of marriage and white-picket fences,” as Ross Douthat of The New York Times puts it. In a period of trending tradwife content and worldwide right-wing efforts to roll back women’s rights, it is understandable that listeners might draw a connection between Swift’s desire for conventionality with a broader cultural push toward traditionalism for women.

But it’s important to distinguish cultural context from personal expression. Swift has expressed a desire for marriage and children on every album besides Reputation (2017). On Red’s “Starlight,” she sings: “We could get married / Have ten kids and teach them how to dream.” On folklore’s “peace,” she addresses her lover: “[I’d] give you my wild, give you a child.” Lest we forget, this is the same woman who rewrote Romeo and Juliet on “Love Story,” so that the story ends with their happy engagement instead of suicide. Matrimony and parenthood are not new themes, and they certainly aren’t anti-feminist.

Perhaps it is fair to expect some awareness of her position as a role model for young women, and that she might be inadvertently aligning herself with the Right’s ongoing effort to perpetuate a return to traditionalist roles for women. But at a time when Swift is publicly engaged, after a lifetime of dreaming of it, it makes sense that these themes would appear more explicitly and more often in her music. We should ask: Why are we so quick to suspect everything this woman does? And who are we to discourage a musician from exploring her own happiness artistically?

I would stand to argue that a Taylor Swift album devoid of romantic disappointment, and instead full of love and optimism, feels like a quietly rebellious subversion of audience expectation. Swift has a history of being pigeonholed as a vengeful ex who only writes about heartbreak. This she herself has called “a very sexist angle to take.”

It is true that she does have a lot of breakup songs, though. The first song I put on after my breakup in February was “loml.” (For a man whose face I now struggle to remember, I do appreciate the overreaction and irony now in that song pick. To paraphrase “I Don’t Wanna Live Forever,” I presently think I dodged a bullet rather than lost the love of my life.) My best friend Daisy and I spent that whole night in her Edinburgh bedroom streaming Taylor Swift like we were the ones getting paid for it. It was both because her music felt apt and because it was comforting in its familiarity.

When I wondered aloud why we bother with love if it never lasts, Daisy suggested something that stuck: maybe we could take Taylor Swift’s bouncebackability as our inspiration. How can someone fall in love so deeply, so often, and each time have it go so wrong, but keep coming back for more? How do you write “All Too Well” at 22 and ever date again? How do you write, “You shit-talked me under the table / Talking rings and talking cradles / I wish I could un-recall how we almost had it all” and then, two years later, be happily engaged to someone else? It speaks to a compelling resilience, a refusal to let disappointment kill possibility.

Sure, people are definitely way too parasocial with Taylor Swift. She built her brand on relatability, and her stark vulnerability around her love life created an emotional accessibility that inevitably led to public overinvestment. Yet, it is important to acknowledge there is no other public figure in our times whose romantic history has been so intimately and consistently documented in real time through art. And every time she’s been down, she’s gotten back up.

So, what is Taylor Swift’s cultural value? I think part of it is the example she sets – not as a perfect artist, or perfect feminist, or even perfect partner – but as a relentless art-maker and relentless lover. While her discography is, in my assertion, more miss than hit, it’s hard not to be inspired by her unwavering pursuit of passion, love, and success. Compared to the bleak introspection of The Tortured Poets Department, The Life of a Showgirl’s celebratory tone feels less like a regression and more like a hard-won evolution. I can’t say I enjoy or relate to a single track on it, but even a weak album can provide emotional refuge. Its celebration of happiness and love offers something worthwhile: hope, still, for the tortured poet.