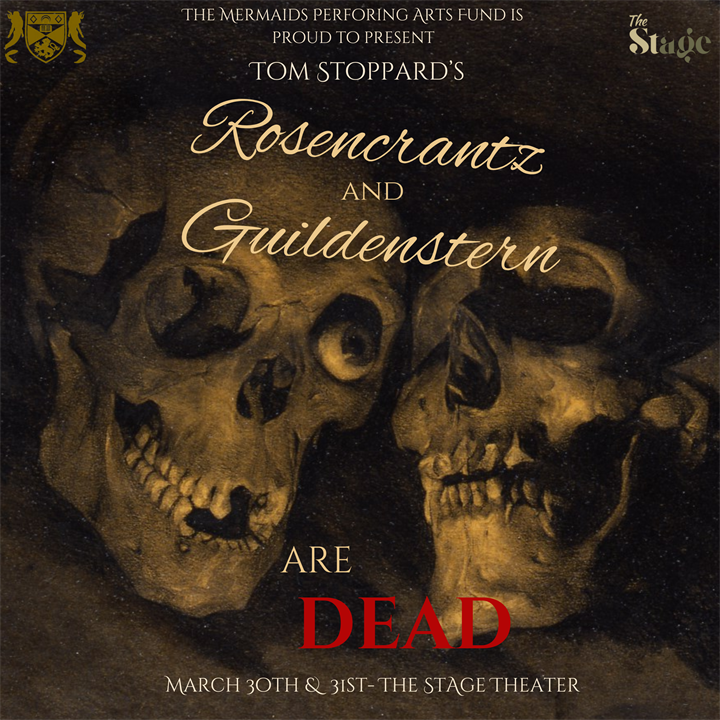

Theatre Review: Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead

A Mermaids Production

30/3/25 - 31/3/25

Directed by Willa Meloth and Annalise Roberts

Produced by Kritvi Gupta

Written by Tom Stoppard

Review by Noor Zohdy

‘There must have been one, a moment, in childhood when it first occurred to you that you don’t go on for ever. It must have been shattering—stamped into one’s memory. And yet I can’t remember it. It never occurred to me at all. What does one make of that?’

In the fullest performance of life, upon an unbroken suspension of disbelief, a world in which everything might present itself in unanticipated surprise—life itself is unthreatened, mortality makes no sound. And yet, if we were to take to the margins, to question belief at every stage, to fiddle with the performance of a life as it is lived, does not the presence of life—as it once stood by faith—jar one suddenly as absurdly out of place? For if we know all this, hasn’t something already gone out? And yet, of course, we do; with mortality on the periphery of human self-definition, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are no more fated than ourselves. Playing with the themes of its canonical source, the Mermaids Production of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead staged the perplexed immediacy of mortal action: for, as it acts in one breath unaware of its deterministic outcome, it recalls itself, in another, through the languishing irony of ever-retrospective fatality.

‘They had it in for us, didn't they? Right from the beginning. Who’d have thought that we were so important?’

‘But why? Was it all for this? Who are we that so much should converge on our little deaths? Who are we?’

Upon a regressive plot of tatulogical cyclicalities, the play pivoted around the existential indecision of two central characters in a manner reminiscent of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. The scenes dripped in the excess of performance—from Hamlet’s (Jack Dams) loquacious lunacy (his Shakespearean register oddly and yet essentially out of place) to the private, uncertain repartee of his two childhood companions (Rosencrantz, played by George Rook; and Guildenstern, played by Freddie Crawford) in their self-defeating search for order and meaning:

‘Each move is dictated by the previous one—that is the meaning of order. If we start being arbitrary it’ll just be a shambles: at least, let us hope so. Because if we happened, just happened to discover, or even suspect, that our spontaneity was part of their order, we’d know that we were lost.’

But aren’t they? For, from the beginning, the titular characters are trapped in another play, and the title anticipates their fixity within it. But in their awareness, in their apartness, they sustained a curious aside to the theatrical process; as Guildenstern proclaimed helplessly from the floor—

‘I’ve lost all capacity for disbelief. I'm not sure that I could even rise to a little gentle scepticism. ‘

And so, as half-reluctant performers, how do we act? What is true sincerity? Between the layers of careful performance and unthinking spontaneity, defeated indecision and vehement defiance, George Rook as Rosencrantz and Freddie Crawford as Guildenstern performed with the exacting candour—the razor’s edge of gravity and nonsense that Stoppard’s play requires. Their performances crafted a play starkly living in the wake of its own end, keenly aware of the ironic performativity inherent in unforgetting mortal existence. The two performed with the careful precision and the pure humour of two clumsy, unremittingly mortal voices constantly battered by the paradox of authenticity and facade in a deterministic universe. They are helpless, confused, and yet, I held by them to the end; as if, after all, I expected things to go differently.

‘Where we went wrong was getting on a boat. We can move, of course, change direction, rattle about, but our movement is contained within a larger one that carries us along as inexorably as the wind and current…’

And yet, as the title anticipates, in Shakespeare’s play, we see nothing of the deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. The news is retroactively delivered from the line delivered by the English ambassador from which Stoppard’s title takes. Across the clattering chaos of the performance, the two carried their fate in hand. And yet, how it all appeared thrown into question as once more Rosencrantz flipped his coin, forgot his sentence, Guildenstern threw up his hands in exasperated abandon. But then—always, somehow, in their heights of feeling, the whole thing wavered; it suddenly seemed so frightfully pointless. The paradox of mortal knowledge was acute throughout: the greater the clamour, the greater the despair, the sillier it all seemed. But amidst the comedy and frenzy, with disbelief and mortal urgency, their searching earnestness drew the performance taut with steadfast humanity.

The Player (Kiera Joyce) flashed upon the performance with an exquisite dancerly step; her histrionic comedy masterfully kept the play on the brink of its own self-knowledge. One of my favourite moments was when Guildenstern attempted to kill The Player, only for him to spring back to life, revealing the knife Guildenstern yielded to be a retractable prop blade. In The Player’s graceful leap to his feet and his lackadaisical rush about the stage, the significance of Guildenstern’s act was complexly diminished and called into sudden question. The retractability of the act reflected the performance of these two ghostly characters—half-murdered, half-living.

And how do the two die? Precisely faithful to their predecessor—just as in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, they disappear, unsought, from the stage. Yet, here, their marginality in the original was recast anew; in Guildenstern’s side-step from the spotlight as it fell dark, I saw an essential poignancy, a sudden pitch to the seeming insignificance of the two throughout this play and its parent text. In their very silence, in their very ephemerality, they, like the child ever-conscious of their mortal condition, were dead, it seems, from the very start:

‘Death is not anything... It’s the absence of presence, nothing more...the endless time of never coming back…a gap you can’t see, and when the wind blows through it, it makes no sound.’